Suppose you want to fit an ordinary least squares model to a set of points in $\mathbb{R}^2$, but you zoned out during statistics class and now you’re stuck on a desert island. In fact, all you have are a wooden board, a hammer, a bunch of nails, some good old zero-length springs, frictionless cloth loops, and a frictionless rod.

Pretend your wooden board is the plane, and decide on a grid system. Then nail each of your data points into the board. Attach to each nail a zero-length spring that can only move up or down. On the other end of each spring place a little cloth loop, for hanging something.

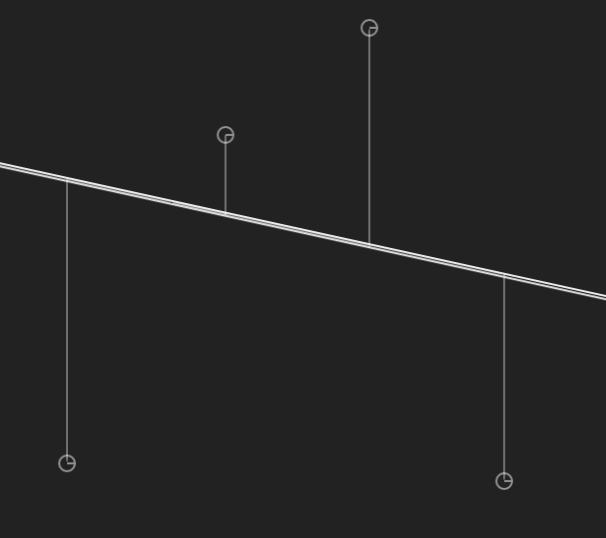

Now imagine taking the long frictionless rod, and threading it through each of these loops. The equilibrium state it reaches is the line of best fit!

I made an interactive demonstration of this, but it only works in full screen (click to open):

You can drag on the rod, but you have to be very accurate with your mouse. Refreshing the page gives a new random set of points.

One can derive the optimality of the equilibrium state using the fact that the potential energy of a zero-length string extended by distance $u$ is $\frac{k}{2}u^2$, where $k$ is Hooke’s constant. It doesn’t matter what Hooke’s constant is, as long as it’s positive, so we can set it to $k=2$ to eliminate the fraction. One ends up with the total potential energy of the system $\sum_{i=0}^n (Ax_i - y_i)^2$, where $(x_i, y_i)$ are the points (nails), and $A$ is the function that tells the $y$ value of the rod at point $x_i$. We know $A$ is linear since the rod is straight. This happens to be the loss function for ordinary least squares!

Squaring is convex, and $Ax_i -y_i$ is affine. Composing convex functions with affine ones gives convex functions, and adding convex functions gives convex functions. So the whole loss function is convex. If there is more than one data point, it is strongly convex, and the only minimum in the system is the unique global minimum. In other words, the resting point for the rod attached to the springs is the (unique) line of best fit. Hooray!

Why do the springs have to go straight down? Well, they don’t have to! If you loosen that restriction, then you end up with a Total Least Squares regression instead. A TLS model allows for error not just in the $y$ axis, like OLS, but also the $x$ axis. For example, suppose you took noisy x-y plane GPS measurements along a straight trail, and you wanted to estimate a line through the actual trail. Since there is error on both $x$ and $y$, one can use TLS. (If we assume the variance on $x$ and $y$ here is the same, then one actually drops into a subcase of TLS called orthogonal regression.)

The example was made using planck.js, which is a nice javascript port of Box2D, although it was sorely lacking in documentation. For instance, I couldn’t find an easy way to run my demo outside of fullscreen.

This setup came from the book, The Mathematical Mechanic, which is full of perversities like this.